Jason Rezaian: Previously on 544 Days:

Yegi: So I thought to myself, oh, my God, maybe Jason is underneath and they're torturing him and they want me to see that.

[news clip] The Islamic Revolutionary Guard in Iran is both revered and feared.

Yegi: Anyone with the gun is obviously more powerful than the one with no gun. So as long as someone holds a gun on your head, that makes you in comparison, powerless.

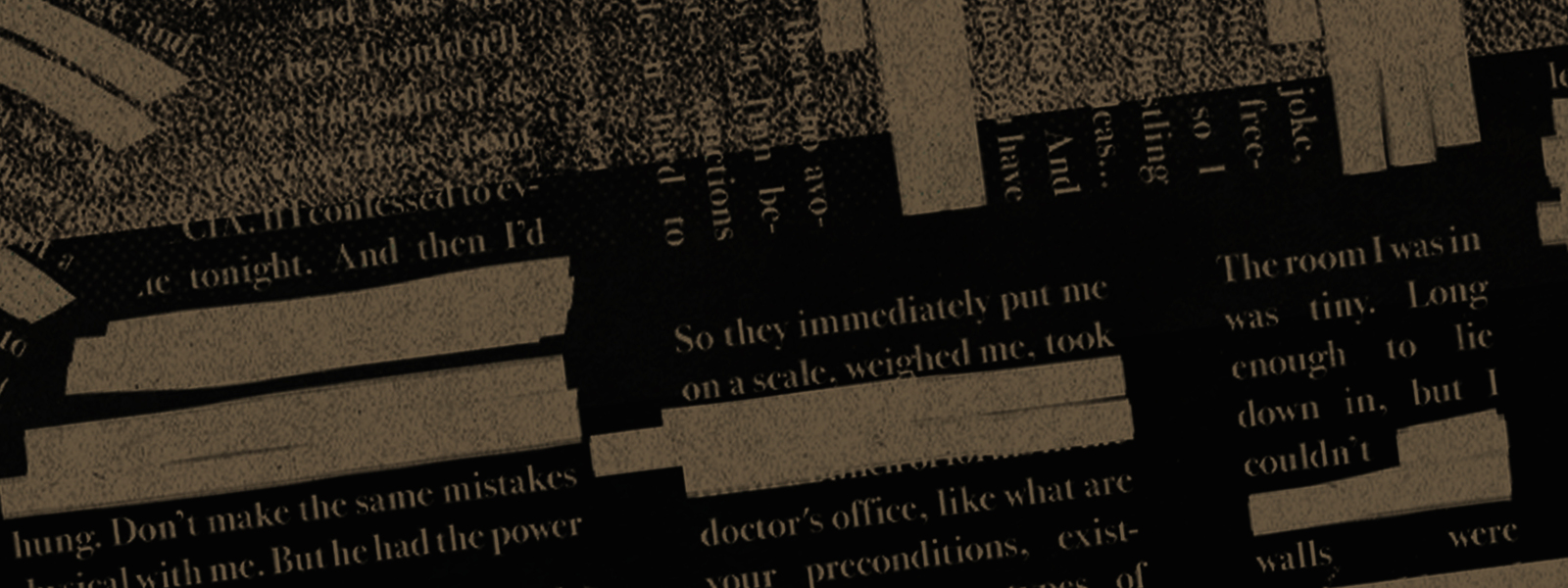

Jason Rezaian: I guess it's natural that people want to know if I was tortured in Evin prison. And it doesn't have a simple answer. There have been plenty of well-documented cases of physical violence used on prisoners in Iran, including political prisoners. Some have even died in the process. In my case, I wasn't physically abused. Like I said in the last episode, my captors loved to remind me that "here is not Guantanamo," as if they were trying to convince me that they would never sink to the level of the US in the way they treat their prisoners. Actually, they called us their guests. It took me a while to realize that I was being tortured, just not in a way that left bruises. I was deprived of sleep and food and medical attention, and I was told that my family thought I was dead and that if I didn't confess, I'd be executed. That's all torture. Just being held in solitary confinement can cause long-term psychological damage. That's why the U.N. considers solitary confinement for anything over 15 days, to be torture. During my time in solitary, I lost a lot of weight: 40 pounds in 40 days. I also got weird headaches, eye infections, pain in my balls. I'd suffer from hallucinations, certain that the walls and floor of my cell were moving. I was not in a healthy place. If you want even more details about this, I wrote a whole memoir about it. It's called "Prisoner." Yes, that's a plug. You should buy the book. But for now, I'm going to take this podcast into new territory, because my story is just one part of this.

Jason Rezaian: I'm just going to set my phone to do not disturb. Mom, have you turned off—?

Mary Rezaian: Oh, I didn't think about that.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: That's my mom, Mary Rezaian. And she's got a story, too.

Mary Rezaian: I had a phone call from you brother and my first thought was, OK, what would dad do?

Jason Rezaian, narrating: I'm Jason Rezaian and this is 544 Days. Episode 3: The Rezaians confront a challenge few American families ever face: how to free their loved ones from a prison halfway around the world.

Ali Rezaian: Hey, real quick question, Jason. Can you, before we get started, can you can you just run down who else you're talking to and who you plan to include in this before we get going?

Jason Rezaian, narrating: That's Ali, my brother.

Ali Rezaian: If you plan on, like, cutting it up and whatever, right, you know, you might want to have somebody talk about what a great guy Jason is.

Jason Rezaian: Well, that's what we brought you on.

Ali Rezaian: I don't know. I might not be, I might not be objective enough.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Like any big brother, Ali's been giving me shit since we were kids. But when I was detained in Iran, he made up for it. I mean, listen to some of the things that people say about him.

Man: I want a big brother like Ali.

Different Man: He just was relentless,

Woman: Wonderfully relentless.

Doug Jehl: Relentlessly focused.

Speaker: Relentless.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: You get the point. Most people who were taken hostage somewhere in the world don't have advocates like my brother. His relentlessness—that's one of the main reasons I'm not still inside Evin Prison now. Ali's a biotech consultant. He traveled for work. But unlike me, he was pretty happy staying at home in California.

Ali Rezaian: I offered to have the wedding somewhere else.

Jason Rezaian: That's true. You did.

Ali Rezaian: Yes, I did.

Jason Rezaian: He offered Rome.

Ali Rezaian: The one in Rome, well it's not the same hotel. It was an Intercontinental with a garden up on top of the bar, the charcuterie there is amazing. This charcuterie was as big as the table I'm sitting at right now and with a view down over the Spanish steps. Yeah.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: That's Ali. At the time of my arrest, he was taking a day off at home in Marin County.

Ali Rezaian: And I started getting these telephone calls from an unlisted number. And I just kind of ignored them because everybody who I was working with knew that I wasn't working. So I was like, this is just junk. But then I received a text from Doug Jehl over at The Washington Post. He introduced himself, said that he was your boss, and that he wanted to talk to me. So then I called him back and I think he gave me some information that you guys had been taken. We talked about it and kind of said, OK, hopefully this isn't going to be something that's going to take that long. And like I say, he said , you know, we don't know much, so we're going to get back together again in a couple hours.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Doug Jehl was my editor at The Post. He had gotten a call earlier that day from another journalist in Iran who'd heard that Yegi and I had been arrested. Doug told Ali not to panic.

Ali Rezaian: Yeah, I mean, I think for the first fair bit, we were like, all right, you know, Jason's been brought in to talk before. We didn't know the extent of what had happened at your house. And so I think it was kind of like, you know, this is what he signed up for. They're going to take him in, they're going to ask some questions, and they're going to kick him tomorrow or the next day. And I think the really the thing that made it less concerning to me, especially at first, was just that I kind of knew what you covered. And you and I have talked about it a whole bunch of times and I knew that you weren't like, you know, digging around into anything you shouldn't have been right? You were following the rules.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Even though at first he thought everything would be fine, as soon as he learned about my arrest, my brother knew he needed to call my mom.

Mary Rezaian: When I first heard, I was certainly concerned. And I fell back on the, what turned out to be, the false assurance that if anything happened to you, there would be people there who would be able to arrange things to get you out.

Jason Rezaian: You talk about your worry gene, and I would argue that in your later years, some of that's gone out the window. [laughs]

Mary Rezaian: You mean you think I'm reckless?

Jason Rezaian: You said it, not me.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: If my mom seems pretty easygoing about the idea of her youngest son getting picked up by the security apparatus of a hostile government and thrown in prison, well, that's my mom. It takes a little bit more than that to get Mary Rezaian riled up. She's an explorer at heart. She's been pushing herself out of her comfort zones her entire adult life.

Mary Rezaian: I was always interested in foreign things and drawn toward foreign people and drawn toward your dad.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: My mom grew up in a little town called Warrenville, Illinois. It's right next door to Wheaton, home of evangelical Wheaton College, where Billy Graham got his start. It's only 30 miles from Chicago, but it felt like a million miles away from the kind of life she dreamed of.

Mary Rezaian: I always felt like an odd fish. All my life, I was always the shortest kid. I had to wear glasses from the time I was six. My parents were divorced in the '40s. I mean, they were—

Jason Rezaian: You were into foreign Muslim dudes?

Mary Rezaian: No, no, no. Actually, I was not into foreign Muslim dudes until I met your dad.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: My dad, Taghi, grew up in Mashhad, Iran's holiest city. It's always been a conservative place. Things like dancing and hanging out with members of the opposite sex were frowned upon. But dad wasn't wired like that. He dreamed of going to America. It was something a growing number of young Iranians were starting to do at the time. Dad's dad, my grandfather, was a wealthy and influential figure. He supported my dad's dreams. So in 1959, Dad left Iran to study at Georgetown University here in Washington, D.C.. Sometimes I think about what that must have been like, going from a strict Islamic society to the capital of the United States. It must have been mind boggling. After only a few weeks here, Dad decided he wanted to go home. America was just too different. My grandfather, though, wasn't having it. He'd spent too much money and social capital to send my dad to America, arranged for him to go to a different school, one that some other students from Mashhad were already attending. So that's how my dad became probably the only person in history to transfer from Georgetown to Napa Junior College. After finishing a two-year course there, he enrolled at San Francisco State and that's where he met my mother. She'd escaped to California from the Midwest.

Mary Rezaian: So I was going to summer school and so was your dad. And we met in the library. I always thought of myself as someone who, in all probability would not marry, definitely would not have children, definitely would not be a homemaker, and would have to find a career overseas. So when I met your dad, my life took a really different turn.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: She'd never met anyone like him before. He was fun, charismatic and driven. The fact that his English wasn't great probably made him even more attractive. Taghi and Mary were getting serious, but her mom in Illinois was not on board, not at least until she could meet these Rezaians from Meshad. That was her condition. So in the spring of 1967, they did something that sounds pretty incredible now, but was actually easy for Americans back then: they hopped on a plane for Iran.

Mary Rezaian: So we visited historic sites and we spent five days with Taghi's family in Meshhad. And I fell in love with the country as I had fallen in love with the man. We married. We had children. We had a house. We had a house full of Iranian relatives. And that's how you guys grew up.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: My brother came along in 1970. I was born in 1976, the Bicentennial AND the Year of the Dragon. Dad opened a Persian rug shop north of San Francisco, and his business thrived. A couple of times a year. He'd go back to Iran on buying trips. He bought a big house in Marin County and he always drove a fancy car, usually a German one. He was living the American dream. Then something happened that would change our lives forever.

[news report] Some 60 Americans are now beginning their sixth day of captivity inside the US embassy in Tehran.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: In 1979, I was only three, so I don't actually remember this, but you probably know something about it. Iran had gone through a cataclysmic revolution. The Shah was exiled in January of that year and the Islamic Republic was born soon afterwards. The country went, suddenly, from a monarchy to a theocracy. And then in November, Iranian militants took dozens of American diplomats hostage at the US embassy. What I do remember from around that time was the way that my dad's relatives would shout at the TV, angry at how the Iranian people were being portrayed.

[news report] Good evening. It's been 13 days since Iranian students stormed the US embassy in Tehran and took 62 hostages.

[news clip] The militant students holding the hostages hardened their terms today. They rejected the idea of having the Shah leave the United States for any country other than Iran.

[news clip] The situation was potentially explosive as Iranian marchers were met by angry jeering crowds of people who shouted "Iranians go home" and "USA all the way." The crowds burned Iranian flags . . .

[shouting] Go home! Go home you fucking—

[shouting] Let our people go!

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Iran went from being a place most Americans had only vague ideas about to being our number one enemy almost overnight. Suddenly no one was interested in buying Persian rugs or anything else from Iran. My dad said he went from doing $400,000 in sales the month before the hostages were taken, to zero for the next six months. No customers. Someone even shot bullets through the massive window in the front of the store. My dad never replaced it as a reminder of the bitterness of that period. When people used to ask him where he was from, he'd say he was Iranian by birth and American by choice. But at the time, a lot of people didn't think it could be both. Some people still don't. When the hostages were finally released, all 52 of them, businesses all over the country scrambled to send them welcome home presents.

[clip of Charles Osgood] The hostages must have the greatest array of gifts and surprises since Queen for a Day. Already in Wiesbaden, sent there by plane, they've got 52 lovely live lobsters from Maine.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: That's Charles Osgood on CBS News in January 1981. He used to do this rhyming news shtick every week.

[clip of Charles Osgood] A West Coast rug dealer. Born in Iran, wants to prove where he stands in the best way he can. A thousand bucks off on a rug, small or large.

[clip of Taghi Rezaian on the news] I will send 52 gift certificate and they can call me or write to me, I'll send it free of charge.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: That's my dad, Taghi Rezaian, although on the screen they misspelled it, Tashi. When he shipped the rugs to the returned hostages, he included a certificate in the package, it said: On behalf of Iranians, I apologize for what you've endured and as an American, I welcome you home. I still have the thank you notes we got from dozens of the hostages who received those rugs. In April 2011, my dad died. He was 71 years old. Along with a couple of cousins, Ali and I did the ritual washing of his body, a sacred act in Islam. Dad had done it for several of his relatives in California, and he would have done it for us. If I told you it was the most important thing I'll ever do, I wouldn't be exaggerating. It brought me closure and peace that I'm not sure I could have gotten any other way. We buried him in a cemetery that's the final resting place for much of Marin County's original Iranian community. He's next to his sister and near other Rezaians. His health had been declining since a car accident a couple of years earlier but I knew it was something else that finally broke them. Just four weeks before Ali's son Walker died suddenly. You've gotten the H1N1 flu. Walker was only five years old. I don't think I need to explain how devastating the loss of a child is. Maybe it's impossible to put into words. I'm only telling you because you should be aware of what came before my ordeal: Walker and then dad. Our family dynamics were completely upended just three years before I was thrown in prison. After dad's death, my mom had a big decision to make. She didn't want to stay in Marin. A lifetime of memories were now shrouded in sadness. So at age 69, her wanderlust still intact, she decided to come live with me. In Tehran.

Mary Rezaian: Having an opportunity to move away from California gave me, I suppose you could say, a new lease on life. I was, I was moving out into the world as a single person rather than as a member of a couple. Because we'd had, what, 45 years together? And that was a real gift to me.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: My mom moved to Tehran and we became roommates. It actually wasn't that bad. We had some fun. We lived together for a year and a half until Yegi and I got engaged. Mom decided it was time to move again.

Mary Rezaian: I was very clear that I did not want to move back to California or the United States, for that matter, because I was living the dream. You know, my dream had always been to live overseas.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Her next move was Istanbul, a city she'd always been curious about but had spent hardly any time in. So that's where mom was in July of 2014 when she got the call from my brother that Yegi and I had been detained.

Mary Rezaian: It was Thursday morning, the 24th. I was awake at 7:30 in my apartment in Istanbul. I had a phone call from your brother, and my first thought was, OK, what would dad do? What would your dad do?

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Coming up: my mom gives Iran's Supreme Leader a good talking-to.

Mary Rezaian: It's how a mom would talk to her kid. And yet it was an angry mom coming across telling the Supreme Leader, let my son go.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: The first thing my mom and brother did after hearing about our arrest was start working the phones, they started calling my friends and colleagues in Iran. Ali tried contacting people in government and influential Iranian experts—anyone who he thought might be able to get me out. Mom followed his lead.

Mary Rezaian: Well, I stayed in close contact with Ali, and he pulled together a task force of several people. They were journalists, they were Iranian activists, some people who had themselves spent time in the same prison.

Ali Rezaian: Hello, this is Ali. Is anybody there?

[voices on the phone]

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Ali would sit at his kitchen table, where he held his conference calls with the task force.

Ali Rezaian: We wanted to catch up, first of all, on just some background, what's going on, kind of current state based on what we know from Iran and then work through that and then try and come up with, some brainstorm some ideas.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: A friend of mine videotaped some of those meetings.

[man on speakerphone] That's been pretty standard procedure with just about everybody they've picked up. The difference with Jason's case seems to be that they actually haven't formally charged with anything. With other people, they've tended to formally charge them and then say all those things afterwards.

Mary Rezaian: In the early days, we still hoped that it would be possible to go through back channels and have you released.

Jason Rezaian: Really what you're talking about is . . .

Mary Rezaian: [unclear]

Jason Rezaian: Yeah. You know, nepotism. And, you know . . .

Mary Rezaian: Who do you know?

Jason Rezaian: Who do you know?

Mary Rezaian: Who do you know? Who did your best friend know, who works at Evin Prison or, you know, has an in with a certain ministry, you know? Immediately when there's any kind of an issue or crisis, Persians go to that mode and so they try to work—I don't know if you'd call that work the system—but to work things out.

Jason Rezaian: That's exactly what you'd call it. Yeah. I mean, you try and, you know, you understand that there's always another . . .

Mary Rezaian: There's always another way. For Persians, Iranians, there is always another way around.

Jason Rezaian: You know, I mean, dad used to say always remember the golden rule: I got the gold, I make the rules.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Although my mom thought I'd get out soon, the thing that made her really worry was my health.

Mary Rezaian: I immediately started sounding the alarm about your blood pressure, which I knew was going to be sky high. And my expectation was that when they arrested you, they didn't bother to pick up your pills from the house.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: It's true. I've been on blood pressure meds since high school and when we got arrested, they didn't bring my pills. At first, my captors wouldn't let me see the doctor to check my blood pressure or get the medication I needed. I did the best I could to stay calm, knowing that getting too worked up might kill me.

Mary Rezaian: So I started making a lot of noise. My fear was that you might have a heart attack or stroke because of the stress.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: For the first few days, news reports about my arrest were pretty low-key and my family hadn't issued a statement yet. And the experts they were talking to thought that it should stay that way.

Mary Rezaian: In the initial days and even into the weeks, I think there was this concern that if we started putting pressure, it would make the situation worse for you and Yegi. I don't want to say it felt like we were flying blind, but we really didn't know how you both would be treated.

Jason Rezaian: You can say that you were flying blind, because you guys were flying blind. I mean, there's not a handbook for this kind of stuff.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: The question of when, or if, the family of a hostage should go public is incredibly contentious. You're getting advice from all directions: government officials, self-proclaimed experts, journalists—and this idea that coming out and demanding the release of family members could somehow make things more dangerous, that's a widespread and deeply-rooted belief. The thinking goes, if the people holding your loved one know that anyone cares, the price will go up. But as the days dragged on, it started to become clear that Iran wasn't just going to quietly let us go. My family had to decide what was the message they wanted to send to Iran and what tone should they use: polite, demanding, or some combination?

Mary Rezaian: And so in an effort, I think, to finally come out with the messages that we wanted out in the media, they asked me to do a video.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: They in this case are the Iranian experts and expats—the task force. So less than a week after my arrest, my 71-year old mom sat down in front of a camera in her apartment in Istanbul.

[clip of Mary Rezaian]: Salam. [speaking in Persian]

Jason Rezaian, narrating: She's speaking in Persian, wishing them a happy end of Ramadan. My mom's wearing a white headscarf and green dress. Her audience is the government of Iran, so she wants to look respectful.

[clip of Mary Rezaian]: [speaking in Persian]

Jason Rezaian, narrating: She says: I'm Jason Rezaian's mother.

[clip of Mary Rezaian]: On the night of Tuesday, July 22nd, my son Jason Rezaian and his wife, Yeganeh Salahi, were both arrested in Iran. It has been more than seven days and they are still being held without charge. I do not know where my son and daughter-in-law are. As a mother, I am extremely worried for their well-being. Jason uses medication for high blood pressure. Without it, his health is dangerously compromised. I love my son and daughter and I am proud of their commitment to journalism. I know their standards for truth and excellence in journalism guide them both professionally and personally. I humbly ask those who continue to detain my son and daughter to please release them, and allow our family to be reunited and my fears for their safety to subside.

Jason Rezaian: What was it like for you to deliver those lines? And you did some of them in Persian. You know, you made an appeal to the Supreme Leader. So you can talk about what—

Mary Rezaian: [speaking in Persian] which is how a mom would talk to her kid, rather [Persian].

Jason Rezaian: Right.

Mary Rezaian: And after the fact that was pointed out to me. And yet it was an angry mom coming across, telling the Supreme Leader, let my son go. You know?

Jason Rezaian: So I mean, what did it feel like to sit down, and you hadn't done a lot of reading of lines since high school musicals—what was that experience like?

Mary Rezaian: The experience of doing that felt strange. You know, I've always tended to be somewhat of a private person and. Yet this was a matter of life and death, and so I had to reach in to find other rusty parts of myself. To do my share. So, yeah. It was weird. It was weird.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: On the night of September 10th, 2014, nearly two months after my arrest, I got some news. Kazem, my interrogator, told me I'd be leaving solitary confinement. I was taken out of my cell, blindfolded as always, and marched into a different part of the prison. I was getting a cellmate. He was a businessman from Azerbaijan. He didn't speak any English and he didn't speak any Persian so I had no idea how we'd communicate. Eventually, we developed a kind of improvised language that featured a combination of English, Azeri and Persian words, and plenty of grunts. And we started to get to know each other. His name was Mirsani. No one explained why this was happening. Had they finally decided it wasn't a threat. Not too much later, a guard came to my cell. He brought me back to the big room I'd been taken to on my very first night in Evin. And just like on that night, there was a guy there who everyone called the Great Judge. By this time I'd been his guest for 52 days. He said to me: your value is very low right now and that is a problem for me. It was the first time any of them acknowledged that I was being held as leverage. And if my value was low, that led me to believe that no one back home was doing much to get me out. He said: to raise your value, I must film you. At that moment, I realized that I was about to join the long list of Americans talking to a camera in hostage videos. I imagined my family watching my forced confession on YouTube. How it would torment my mother, make my brother irate. I wasn't being given a choice. Then things got weird. Kazem and I went shopping. They said I'd lost so much weight that they wanted to get me some new clothes to wear for my hostage video. It was the strangest shopping experience of my life. They took me to an upscale part of town and made me pick out a shirt and pants in a popular menswear store. Then they took me to a florist and a pastry shop to buy gifts for Yegi, who was still in solitary. It made no sense. It was like they wanted me to act out the role of your average middle-class husband on his way home from work. Back at the prison, I got to see Yegi again and we ate some of the pastries. They were so unbelievably sweet after two months of prison food, they made our stomachs churn. When they got me in front of the camera to make my forced confession, they had a script ready for me. They wanted me to apologize to the Iranian people, to say that I'd been undermining the Iranian government, to plead to President Obama to get me out. I zigged and I zigged. There were things I wasn't going to say on camera. But in the end, I made the video. Because, like I said, I didn’t really have a choice. All these years later, the Iranians have still never released the messages they forced me to record. 72 days after our arrest, Yegi was still in solitary. But that day our interrogators brought her out of her cell and sat her down in front of a camera.

Yegi: And then they started asking me questions like how we met. So I had to tell the whole story. Everything I have written so far, like 10 times, I had to say it again in front of the camera. It took like two hours. It was like a really tiring day. And after that, around like 6:30, 7, they brought me back to my cell. When I came back to my cell, I saw my own clothes, the clothes that we walked in with, from our home.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: The guard told her to put those clothes on. Then they brought her back in front of the camera and asked her a whole bunch of the same questions all over again.

Yegi: When the whole recording with my own clothes finished, the two guys, Siamak and Kazem told me that, oh, you are being released tonight. I was like, what? I am going to be released? No, this is not what you promised me. What about Jason? They said, we can talk about Jason.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: They made her sign a piece of paper promising to follow a long list of rules: no working as a journalist, no contacting government officials, no advocating on my behalf.

Yegi: If I follow all the rules and these conditions—and I never forget the sentence—if I behave myself and I am a good girl, I'm going to see you out very soon. Within a couple of weeks,

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Yegi was getting out without me. But they were making it very clear that this wasn't freedom. They'd be watching her. And they kept her passport to make sure she couldn't leave the country. It was October 1st, nighttime, and there was a hitch, our captors tried to call Yegi's parents to come pick her up, but nobody answered.

Yegi: They said, we're going to drive you and drop you somewhere. So then you find your way home? I was like, it's impossible, you can't do this to me. This is like a night, a cold fall night. And I came in with summer clothes, so I was like, you guys have to call my parents. You have to find my parents. I'm happy to sit here, I don't have to get released because Jason's not getting released. I still, I was crying, like begging. I held the door knob. The female guard came and she was like pulling me. And then I never forget because the two assholes told me: oh you are the first person who is being released and doesn't want to go.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Eventually they did track down Yegi's parents. But instead of allowing her to walk out the front door of the prison like a normal person would, they arranged a handoff under a highway overpass. Her interrogator, Siamak, rode in the car with her.

Yegi: And my parents came. They were standing there, I could see them. I couldn't see their car, but I could see them standing right there, my mom and my dad. And then my mom came and we hugged and we cried. And then my parents kept asking, what about our son in law? What about our son in law? And he said, hopefully soon, hopefully soon. You talk about some moments in your life as bittersweet. That moment seeing myself free was not a bittersweet moment. It was just a deeply bitter moment because that meant you're gonna still be there and so many more uncertainties will come our way for a very long time.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: So now it was just me at Evin Prison. My new cell was certainly more comfortable than solitary, but I wasn't sure if the move was a sign I'd get out soon or that I'd be settling in for a long stay. But there was one big improvement, my cell had a TV. Mirsani and I would watch it all the time. And even though it only got the channels of Iran's official state broadcaster, that TV became my lifeline to the outside world. It also became the only way I could get information about my case. One day in late September, I was watching a press conference with Iran's president at the time, Hassan Rouhani, he was at the United Nations in New York City

[clip of Rouhani] [speaking Farsi]

Jason Rezaian, narrating: And then the camera panned to a familiar face from home, Marty Baron, who was the Executive Editor of The Washington Post. And he asked a question.

[clip of Marty Baron] First of all, I just want to take this opportunity to revisit the subject of our correspondent Jason Rezaian and his wife, Yeganeh. I would like to say to you personally that we believe that he deserves his freedom and we ask the government of Iran to release him. And I want to ask you how the Iranian government can justify imprisoning a good journalist—I think, you know, he's a good journalist—and a good person and having him imprisoned for two months and interrogated two months? How is that possible?

[clip of Rouhani] [speaks Farsi]

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Rouhani says he hopes I'm as comfortable as possible under the circumstances, it's not much of an answer, but that's not the point. The point is that Marty Baron, my boss's boss, confronted the President of Iran about my case, on TV. For months, Kazem had been telling me that the Post didn't care about me, that they hadn't said a word in my defense, that they weren't doing anything to free me. Now, finally, I had proof that he'd been lying.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: Next time: Inside the White House, where the Obama administration was hard at work on the Iran nuclear deal, and then my captivity went and fucked it all up,

Wendy Sherman: We tried to keep the two separate for a very fundamental reason: if we put them together, we would have given Iran more leverage.

Jason Rezaian, narrating: And I get to hear a welcome voice.

Mary Rezaian: While we were talking, I kept thinking, boy this call is really, I mean, he's been allowed 10 minutes, 20 minutes, 30 minutes.

Jason Rezaian: Yeah. It felt like a really long call.

Mary Rezaian: It felt like a, it was like, wow, this is great, and what's going on here?